JULIA FOUND THE NOTICE on Tuesday evening, when she sorted through the mail at the kitchen table. As letters went, it was hard to miss. The envelope was large and square, made of thick, cottony, cream-colored paper, and it was addressed by hand in crisp black ink to Miss Julia Dalrymple.

Well, who could resist an envelope like that? Julia lifted it free from the bills and catalogs and charity appeals that had accumulated over the past few days. She turned it over and back again, but she discovered no return address, no postage, no postmark, as if someone had hand-delivered this communication into the mailbox while she was away for the weekend. When she lifted it to her nose, she caught a fleeting scent of violets.

Intrigued, Julia inserted her pinky finger in the corner of the envelope flap. It wasn’t stuck down with glue. Instead, a seal of gold foil secured the flap to the paper beneath. She broke the seal and opened the flap. Again she smelled violets, but only for an instant. You’re imagining things, she told herself in her grandmother’s gravelly voice.

She drew the card briskly from the envelope.

Dear Miss Dalrymple,

The book you requested has arrived at the library. Please present this card at your earliest convenience to the librarian at the reception desk, who will direct you to the appropriate shelf.

Yours sincerely,

The Board of Trustees

Darlington Town Library

GRAN CALLED HER on the telephone while she was heating up leftover pasta for dinner.

“So he didn’t pop the question, did he?”

“For Chrissakes, Gran. What is this, 1952?”

“Don’t use that language with me.”

Julia stood back and watched the pasta bowl rotate inside the microwave. She imagined Gran sucking a long drag from her cigarette, exhaling, tapping the ash into the ashtray on the wood veneer coffee table in her living room, twelve hundred miles away. The microwave beeped. Julia stirred the pasta and added another minute.

Gran gave in first, like she always did. “Well?” she demanded.

“Well, what? We’re not engaged, if that’s what you’re asking.”

“I knew it. I told you. What did I tell you, Julia? You give away the milk for free—”

Julia hung up.

Gran called back a half hour later, while Julia was washing the pasta bowl. “He’s a louse, that’s what. What the hell do you see in him, anyway?”

“You haven’t even met him, Gran.”

“I don’t need to meet him. I can picture him.”

“Oh? How do you picture him?”

“Like a gorilla. A gorilla with a weak chin.”

“Victor does not look like a gorilla, Gran. And he has a totally normal chin.” Julia set the bowl in the drying rack. “Actually it’s a very nice chin.”

“Then why won’t he marry you?”

“Sorry, I don’t see the connection?”

Gran hacked a few coughs. “Chins. Gumption.”

“Gran, gumption isn’t even a word anymore. Lay off, okay? Maybe I don’t want to get married. We only met six months ago. And we just moved in together, new town and everything. That’s a big enough step.”

“And where is he now?”

“He’s at the hospital.”

“Ha. See what I mean?”

“He’s a doctor, Gran. He’s supposed to be at the hospital.” Julia’s phone beeped. She checked the screen. “See? He’s on the other line right now. I’ll talk to you later.”

“Young lady—”

Julia switched calls.

“Victor! Hi. Sorry, I was on the other line with Gran.”

“No worries. All settled in?”

“Yep. I had the leftover pasta for dinner. You? How’s the ER tonight?”

“Quiet. Thank God.” Victor yawned loudly in her right ear, where she’d stuck one earbud. The other dangled on her chest. She imagined Victor in his blue scrubs, sprawled on one of the chairs in the break room. Gran pictured a gorilla because he’d played basketball in college, but that was Gran for you. Victor did have long arms, though, and his legs probably extended halfway across the room from where he sat. Julia knew his exact slumping pose, the shape of his wrists where the sleeves ended, a few inches too short.

“That was some weekend,” Victor said.

“It was amazing.”

Julia looked around the kitchen and saw smudge of pasta sauce on the ceramic spoon rest next to the microwave. She took it to the sink and washed it, then she wiped down the interior of the microwave for good measure.

“Sooo,” said Victor. “Anything new?”

“Not really. Still haven’t heard back from the newspaper about that job. I’m thinking I might try some of the local shops, just to keep busy. I hate this sitting around the house thing.”

“Whatever makes you happy, Jules. Anything in the mail?”

Julia set the spoon rest in the drying rack and wiped her hands on the kitchen towel. “Actually, kind of strange. I got a notice from the local library.”

“The library? What, some fundraising drive?”

“No. Something about a book I requested.”

“So?”

“So I didn’t request any book. I haven’t even been to the library yet.”

“Maybe it’s for the lady who lived here before?”

“Nope, it’s addressed to me.”

“Must be a mistake, then. Just ignore it.” He yawned again. “Yikes, look at the time. Gotta hop. And listen, I’m going to sleep over here, okay? I’m signed up for back to back shifts because of going away for the weekend. So I’ll be home Thursday night.”

“I know. You told me already, remember? On the drive home.”

“Did I? Jeez, I must be losing it. You’re making me lose it, Jules. Another weekend like that…”

Julia laughed. “Go on back to your patients, Doctor. I’ll be waiting right here.”

“Now that’s something to look forward to. Don’t go falling in love with someone else,” he said, like he always did when he started a double shift.

“I won’t,” Julia replied, like she always did.

Then she hung up the phone and went about all the tasks that human beings do after a weekend away. She unpacked the suitcases and paid the bills; she turned out the lights and locked the front door and set the thermostat a few degrees lower for nighttime, making their small, rented house snug against the New England night. She changed into her pajamas, brushed her teeth, washed her face, slathered on the expensive night cream that Gran, in her wisdom, gave Julia for Christmas every year. Still, as she lay alone in bed that night, waiting for sleep to fall, an unsettling thought came into her head and refused to budge.

I’ll be waiting right here, she’d said to Victor.

Waiting. She was always waiting, wasn’t she? Everyone else was out hustling and pursuing. Everyone else had a talent, an ambition. Victor was a doctor, for God’s sake! He had just started his first year of residency at the Darlington University Hospital and he was going to be an orthopedic surgeon, he said. One by one, her friends from school and from college had declared majors and started careers, real careers. One by one, they were becoming teachers and lawyers and bankers, police officers and artists and social workers. Discovering and pursuing their life’s work.

Only Julia remained without a clue. Only Julia had tried this and that and everything, pottery and accounting and archeology and artisan baking and one harrowing spring as a nursery school assistant, and still went to bed at night with the restless knowledge that something was missing, that nothing quite fit the craving inside her.

Only Julia now stared at the shadowy plaster ceiling of her bedroom and contemplated a morning filled with not much, a day in which she would apply for some position—any position—at one of the shops along Main Street and wait some more. Wait for her future to walk through the door, jangle the bell, and say This is your talent, Julia! This is what you’re meant to do with your life!

But what if that future never arrived? What if she kept waiting and nothing ever came through her door, except Victor?

What if this was all there was? What if she had no talent? What if all she could do was… be?

THE DARLINGTON TOWN LIBRARY was a giant building, built by some philanthropic industrialist during the town’s heyday over a century earlier, according to the plaque outside. It was made of red brick and cream cornice, and you had to drag yourself up a flight of granite steps to collapse, exhausted, at the main entrance. Inside, it smelled of old wood and old bindings, enclosed by an atmosphere of absolute hush and ancient electric lights that flickered in spasms of indecision. Julia had entered this building only once before, when she and Victor moved to Darlington six weeks ago, and that was by mistake. She’d thought it was the post office, which was next door and almost identical.

A gust of February wind propelled Julia up the library steps to the wide double doors of heavy oak. She hauled one open and blew into the lobby. A middle-aged man in a crimson sweater vest looked up from the front desk. He wore thick-rimmed glasses and an aggrieved expression.

“Hello there,” said Julia. “My name is—”

“Could you close the door behind you, please.”

Julia turned and saw that the door had stuck halfway, propped open by the ferocious wind that now tore through the lobby, ruffling all the loose papers. “I’m so sorry!” she gasped. She stepped back and leaned hard against the door until it groaned into place.

The man at the desk lifted one hand from his inbox and the other from his outbox. His eyebrows rose above the black rims of his eyeglasses. “Can I help you,” he said, leaving out the question mark.

“I believe so,” said Julia. “I’ve received several notices in the mail over the past two weeks, about a book I supposedly requested from the—”

“Which book?”

Julia blinked. “I don’t know. The notices don’t say.”

“You don’t remember the name of the book you requested?”

“But that’s the thing. I didn’t request any book.”

“Then why are you here?”

“Because the library keeps sending me notices. At first I just ignored them, but—”

“Nonsense. We wouldn’t send a notice if you hadn’t requested the book in question.”

“Au contraire, mon frère.” Julia rummaged in the pocket of her down puffer coat until she discovered the sharp, thick corner of the library notice. She lifted it free and presented it to the man at the desk. “You see? Right here.”

He leaned forward and frowned at the card. His lips moved as he read. When he was finished, he transferred his frown to Julia. “Well, which book did you request?”

“I don’t know—”

“Ma’am, I can’t help you find the book if I don’t know which book you need.”

“I don’t need any book! That’s the trouble!”

“Then why are you here?”

Julia looked at the ceiling and drew in a deep breath. She held it for the count of three, like her college roommate—a psychology major—had told her, and then exhaled through her nose. Or was it the other way around? In through the nose, out through the mouth?

“Listen to me,” she said in a quiet, slow voice. “All I need—all I want on this earth, do you understand—is not to get any more of these notices from the Darlington Town Library. Is that clear? Take me off your list. That’s all.”

The man sighed patiently. “Ma’am, you’re the one who requested the book.”

Julia stared at the tip of the man’s nose, which was speckled pink. She thought she could hear the blood rising up her neck and into her ears. Now, don’t shout, she heard her grandmother say in that gravelly voice, shouting never helped anything, but the voice came from a distance, and anyway, Julia wanted to shout. She needed to shout. She didn’t care if it helped or didn’t help, if the man heard her shout or didn’t hear, understood or did not.

She opened her mouth.

As the shout rose upward, though, her gaze happened to fasten on the man’s eyes, which still peered at her from above the thick-rimmed eyeglasses, as if he could see better without the lenses in the way.

About the eyes themselves—which were ordinary in all respects, plain brown, neither small nor large, bright nor dull, containing neither speckles nor gradations of color nor mysterious gold flecks—Julia felt a sudden intuition. They didn’t fit. In some peculiar way she couldn’t explain, they didn’t belong to the man who’d been speaking to her just now.

He continued to stare at her, eyebrows raised, waiting for the shout that didn’t come. Like some kind of standoff, only without weapons. Julia wasn’t about to back down. She crumpled the card in her fist. Her chest prickled with heat inside the puffer coat.

“Mr. Spooner.”

The man startled, pushed up his eyeglasses, and turned to his right, where a tall, thin, angular woman stood by the open doorway of an office.

“Dr. Freeman!” He snatched up a pen from the cup on his desk, fiddled it between his fingers, and dropped it back. “I didn’t see you.”

The woman looked at Julia and back to Spooner. “Can I be of service, perhaps?”

“This young lady…” He turned his head to Julia.

“Julia Dalrymple,” she said.

“Miss Dalrymple has received a notice from the library.”

“Several notices, in fact. For two weeks now.” Julia brandished the card in her hand. “There’s been some mistake.”

“Mistake?” said Dr. Freeman. “I don’t understand. The Darlington Library does not make mistakes.”

“Look, I don’t care if the library makes mistakes or not.” Julia lifted her fingers to make quotes around the phrase library makes mistakes. “I just want to stop receiving these stupid—”

Dr. Freeman’s hand shot up, palm out. “Stop! Dalrymple. Did you say Dalrymple?”

“Yes. Julia Dalrymple, number 13 Oxford Street—”

“Mr. Spooner!”

“Yes, Doctor?”

“Why have you not directed Miss Dalrymple to the appropriate shelf?”

“The—the shelf?”

“So she can collect her book, Spooner.”

“But there is no book!” Julia wailed, before she remembered she was inside a library. She glanced swiftly around the lobby and realized, for the first time, that no other patrons occupied it. Or the reading room beyond the reception desk, or what she could see of the stacks. Or anywhere. Except for Dr. Freeman and Mr. Spooner, Julia was alone. True, this was a cold, damp Monday morning, and Darlington was a small college town without any industry of note. But still. You could always count on at least a few people lurking around the quiet, comforting corners of a town library, couldn’t you?

“I can’t leave my desk, Dr. Freeman,” whined Spooner. “Not in the middle of the morning rush.”

“There is no rush, Mr. Spooner.”

“There might be.”

Dr. Freeman heaved a deep sigh, opened a drawer in the reception desk, and drew out a notecard identical to the one in Julia’s hand, except that it was blank. She selected a pen from the cup and scribbled in crisp, black ink atop the card’s creamy surface.

“Here,” she said, handing the card to Julia. “You’ll have to find it yourself.”

“But I don’t want to find it. I didn’t request a book. For the last time.”

Dr. Freeman’s eyes settled on Julia, and these eyes were not ordinary at all. They were narrow and greenish and had the trick of focusing a colossal amount of attention into the small patch of skin right between your eyebrows. She spoke in a firm, quiet voice, just above a whisper.

“Regardless, Miss Dalrymple. I think you’ll find this book immensely fascinating, if you take the trouble to locate it.”

WHICH WAS HOW JULIA found herself ascending the stairs to the library’s third floor, while her footsteps echoed from the cold walls and her breath sent the dust motes swirling in anxious spirals.

This is utterly ridiculous, she told herself, but her legs kept propelling her upward. The air grew colder and damper and lost the scent of books. Just that smell she’d begun to associate with New England itself, a smell she categorized simply as OLD, originating somewhere inside stone and wood and plaster that had marinated together in a bath of four seasons, one by one, over and over, since before Julia was born. That smell. Only this time there was something else, some wispy note, possibly floral. She drew it deep into her lungs as she climbed the steps and landed at last at the top, an attic room that opened out into the round, book-lined walls of a Victorian tower she’d admired on the outside of the building.

Julia looked down at the card in her hand.

Third floor, tower enclave, bookcase D, shelf 3

The handwriting was precise and beautiful and familiar, and Julia realized she had seen it before. She’d seen her own name formed by this handwriting, on the backs of the envelopes containing the library notices that had arrived in her mailbox every day for the past two weeks, without fail, even Sundays.

Julia whirled back to the stairs, but she couldn’t see the lobby from here. Just the pale plaster walls of the stairwell, the color of old linen.

She turned to the tower and started forward.

Through the quiet, in the spaces between the clack of her own footsteps on the tiled floor, a faint noise found her ears. At first she thought it was music, and then she recognized voices, except in a register no human comfortably spoke. She stopped to listen, but the sound faded just out of reach, even when she closed her eyes and strained for it. Mice, perhaps? She opened her eyes and scanned the baseboards of the bookcases. Nothing but the golden patina of wood, uninterrupted except for the small, square, tarnished brass plaques that displayed the shelf numbers.

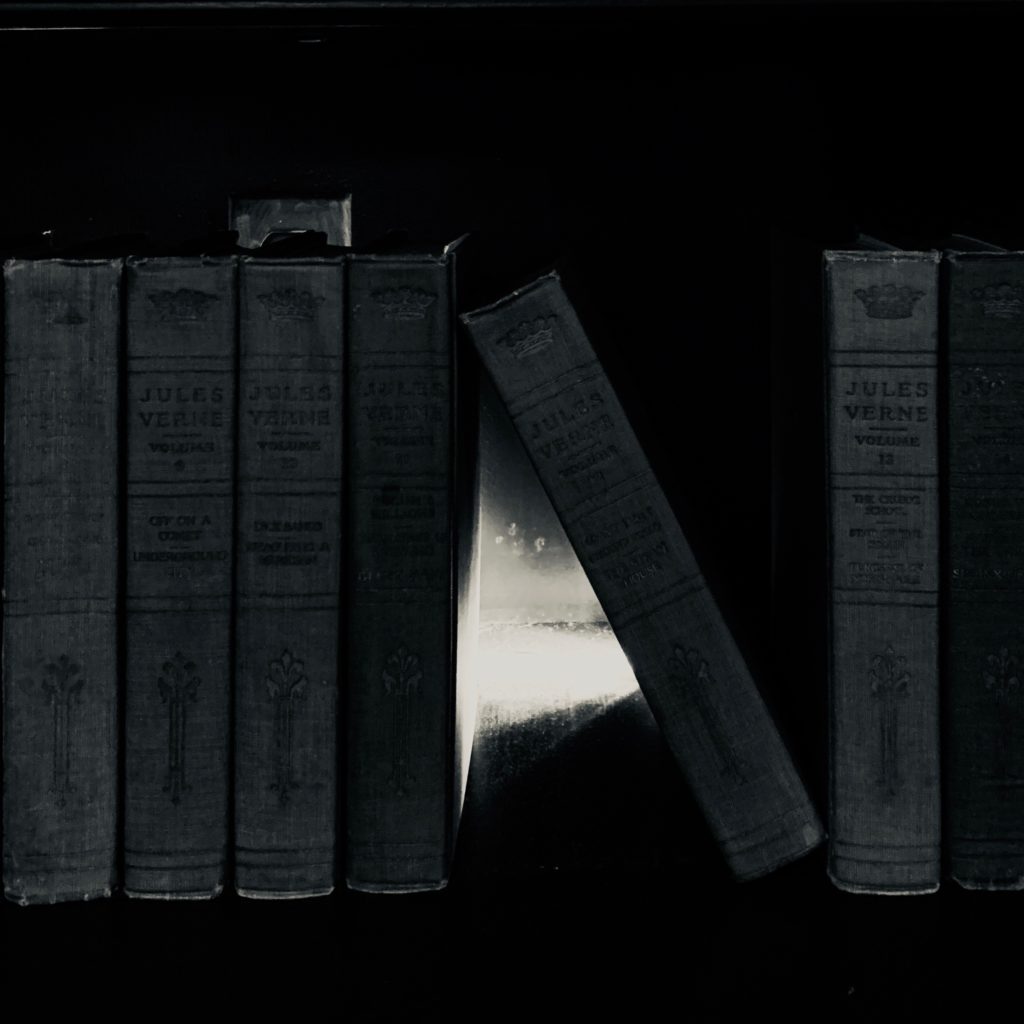

Though a heavy layer of clouds had covered the sky as she walked to the library that morning, the curving space before her was full of sunlight, pouring from the glass dome above. Julia stepped closer until she could read the black numbers on the plaques, the letters on the larger squares in the middle of the topmost shelf of each bookcase. She found bookcase D directly in the middle, curving perfectly to fit against the round tower wall. Inside, the books stood upright in their old leather bindings, red and gold and green. They looked they hadn’t been disturbed in years. Julia couldn’t read the faded titles from where she stood. She wasn’t sure she wanted to. She hadn’t actually ordered a book, after all. Dr. Freeman’s note didn’t even specify which book on shelf 3 was so fascinating as to warrant all this ridiculous fuss.

In fact, if she were sensible, she should just turn around right now and head back down the stairs and out of the library. And she was sensible! Julia Dalrymple was practically famous for her sensible ways. She’d taken a creative writing class once and earned a C plus, which—the teacher informed her—was a generous assessment, since her diligently completed assignments had revealed not the slightest sign of creativity whatsoever. (But your punctuation is superb, the teacher hastened to add.)

What’s the point? Julia thought. Then she said it aloud, in a carrying whisper.

“What’s the point? I don’t even want a book.”

Still, her gaze dragged down the tiny plaques in the middle of bookcase D until she came to shelf 3, which stretched from end to end at about the level of Julia’s eyes. Like the other shelves, it contained a row of uniform books, upright like soldiers, except for a gap near the right-hand side. One book leaned against its neighbor, as if a volume had been removed and never returned. Julia stepped closer and squinted at the titles stamped on the bindings. The book on the left was called A Concise History of the Island of Atlantis, while the book on the right, which leaned against it, advertised Two Hundred and Fifty Varieties of Fern. In the triangle of space between them, a pale golden light gleamed against the bindings.

Julia glanced upward, thinking to find a beam of sunlight streaming from the glass dome that topped the tower, but in the next moment, the sun disappeared behind a cloud. Everything went dim, but the light in the bookcase continued to glow softly between the volumes.

Julia went on her toes and peered at the golden wedge, and as she did so she heard again the noise she’d noticed earlier, the high, delicate voices, except louder. Or maybe they’d been there all along, and she hadn’t paid enough attention? She tried to listen, but she couldn’t distinguish any words, or even tell whether the sound came from one voice or several.

Julia took another step, and another. She reached out with both hands and placed her fingertips on the edge of shelf 4 underneath. She lifted herself again on her toes, right before the gap between the Atlantis book and the fern book. The voices became clearer and deeper. She shut one eye and squinted into the glow.

At first it blinded her. She drew back, but as her eyes adjusted to the glare, she realized she could distinguish shadows, and that the shadows had shape. The shapes became pieces of furniture, and then people among them, both seated and standing. She felt that she was looking through a telescope into a room, and the longer she looked the more she saw, and the more clearly she heard the voices that came from this room and the people inside it.

Well, that’s just impossible, said Gran’s voice, but Gran’s voice was much farther away than the voices in the room, even though Julia still couldn’t quite understand what the people were saying.

She saw the room clearly, though. It looked like the rest of the library, with ecru walls and tall, honeyed bookcases and comfortable armchairs upholstered in jewel-toned paisleys. In the middle of the room stood a table, and on the table lay a tray littered with the remains of an afternoon tea. Cups and saucers, plates of cookies, that kind of thing. On a cake stand of milky green glass rested a large, speckled cake, frosted in white, possibly carrot. Two women sat in chairs next to the table, sipping from their cups, while a tall, slender, fair-haired, bearded man wandered past, holding a plate from which he was eating a slice of cake. He wore a gray checked suit over a wooly red vest; the women wore dresses. They seemed to be arguing about something.

That’s impossible, said Gran’s voice, much louder and as sharp as a thunderclap.

Julia stumbled back from the shelf.

The air was quiet; the voices had faded. She looked around and saw not a soul. She walked out of the tower enclave and examined the wall, looked out the dormer window nearby. The street outside was gray and still and piled with slush from last week’s blizzard. A single traffic light flashed red at the intersection. A few cars parked next to the sidewalk. Julia craned her neck to view the library’s façade, which looked exactly like the exterior she had observed from the outside of the library—red bricks, cream mortar, Victorian tower reaching from the building’s southeast corner. Now that she thought about it, it was strange that the third floor of the tower had no windows, but Julia saw nothing to suggest additional space between bookcase and wall, or wall and something else.

A distant drumbeat rattled her ears. Julia realized it was her own heart, pounding in hard, solid thuds. Her palms were damp. She took in a calming breath—in through the nose, out through the mouth, that was it—and as she inhaled, she identified the floral note she’d noticed earlier, much stronger now.

Violets.

This is crazy, she thought. It’s just your imagination.

She started toward the empty stairwell.

But you have no imagination, Dalrymple. Remember? You got a C plus in imagination, and that was just because the teacher felt sorry for you.

Julia balanced on the topmost step. The tower room lay behind her, over her left shoulder. The violets lingered in her nose.

Chicken, she thought. You’re chicken, that’s all.

Julia put her hand in her pocket and fingered the card Dr. Freeman had given her. She heard that stern, alluring voice: I think you’ll find this book immensely fascinating, if you take the trouble to locate it.

Was it just her nerves, or did the card vibrate faintly against her skin, like an electric charge?

Without quite meaning to, Julia turned to her left. The bookcases still lined the curving wall of the tower; the books still stood upright on their shelves. She counted across until she reached bookcase D, then counted down to shelf 3. She moved her gaze to the right, until she found one thick book leaning diagonally against its neighbor.

A faint golden light glowed from the triangular gap between them.

Damn it, she thought.

Julia dragged herself back to the tower, about as willing as a prisoner to a scaffold. The scent of violets washed over her. She braced herself on the shelf below and went up on tiptoe to peer into the small, illuminated space. As she waited for the images to take shape, she felt her stomach turn over, as if her guts knew something that Julia did not.

The same room. The same table and chairs, but the tea things were gone, and now there were four people in the room, two men and two women. One of them was the tall, slender man with the beard, but he was now joined by another man, shorter and more muscular, dark-haired, wearing a plain suit and matching waistcoat. He was speaking, but Julia couldn’t hear what he said. She strained closer, until her cheekbone bumped into A Concise History of the Island of Atlantis.

Everyone in the room startled and looked around.

Julia gasped.

The dark-haired man turned and stared straight in Julia’s direction. His eyes widened. He set down the glass on the table and strode toward her. Julia drew back.

“Wait!” he called.

Julia whirled around and ran for the stairs.

JULIA TRIED THREE TIMES before she finally got the key in the lock. The front door swung open at last, but she didn’t go inside, not at first. She stuck her head forward and ran her gaze around the walls and the furniture of the small, comfortable living room.

Everything was as she’d left it. The watercolors hung on the wall, the secondhand sofa sat in place, empty and silent. Only Julia was different. Dizzy, rattled. Smelling violets that were certainly not there. When was Victor supposed to be home? Not for another three hours at least. She needed a drink.

She closed the front door behind her, crossed the living room, and entered the kitchen. She took off her puffer coat and slung it over a chair. In the fridge was a bottle of white wine she’d shared with Victor the night before and hadn’t finished. She opened the door and found the bottle and set it on the counter while she rummaged through the cupboard for a wineglass. Her hand was shaking.

She closed the cupboard and reached for the bottle. A New Zealand sauvignon blanc, cheap but decent. Her fingers closed around the neck and froze in place.

An envelope lay in the middle of the counter.

A thick, cottony, cream-colored envelope, addressed to Miss Julia Dalrymple in crisp black ink.