TO BE PERFECTLY CLEAR, Julia did not love to bake. There were people—bakers, obviously—who spent their hours thinking about sourdough bread and cinnamon rolls and cream cheese frosting, who obsessed over the fudginess of brownies and the fluffiness of cake, who obtained visceral pleasure from the kneading of dough and the rolling of pastry.

Julia experienced none of those things. She baked because baking distracted her from things she didn’t want to think about—or worse, things she could do nothing about. Besides, when she was finished, she had baked goods.

Victor’s voice clamored from the phone in her hand.

“Jules? Are you there? Did you hear me? The Darlington Town Library does not exist. It’s closed. I don’t know what’s going on or what that woman was doing there, but I think you should just stay away. Ignore the notices. When the snow clears we’ll…Jules?”

“Sorry,” she said. “Do you remember seeing the vanilla anywhere?”

THE BANANA BREAD WENT in the oven, studded with miniature Ghirardelli chocolate chips, and Julia set the timer. The blizzard made a strange banshee wail around the house, unlike anything Julia had heard before. The pitch reminded her of a siren, except it didn’t follow a siren’s steady, predictable parabola of sound. Instead, this wind rose and fell and thrashed side to side, as if it had lost something it loved. When Julia looked out the window, she saw nothing but white. Like Dorothy’s house, she thought. Picked up by a cyclone and carried away to another world.

She stared at the opaque, swirling white outside the window. The shifting pattern mesmerized her. She’d never seen snow like this. At times, she thought she glimpsed a shadow inside its kaleidoscopic movements, flickering to life only to disappear the instant she found it.

She couldn’t look away; she couldn’t breathe. Every nerve strained toward the whiteness beyond the window glass. Something was there. What was it? Something inside that whirlwind of snow strained toward her with equal longing. She knew it in her marrow.

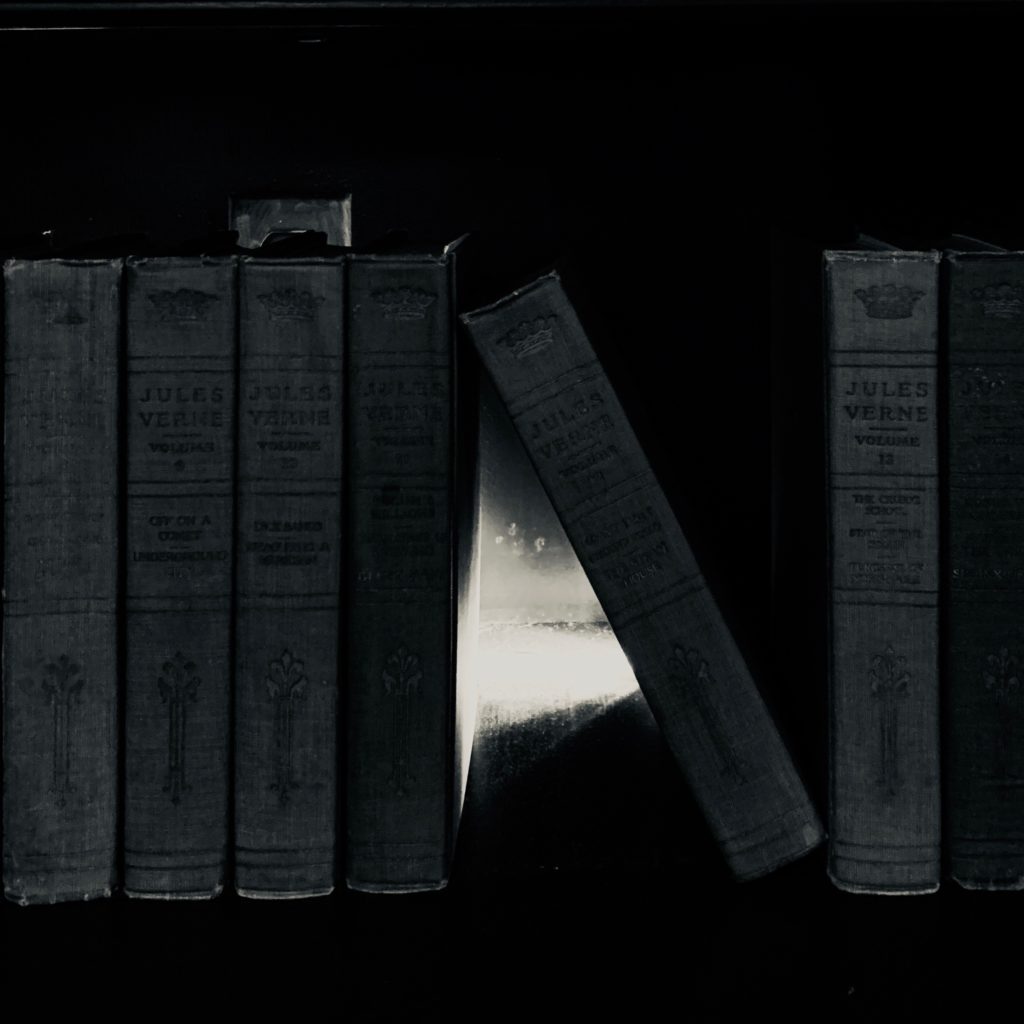

The dream. The dark-haired man, in the room she’d glimpsed between the library books. He stared at her, he was asking for something. He needed something from her, and she couldn’t give it to him. The wail of the blizzard pierced the glass and became the sound of her name.

Julia.

“Max,” she whispered.

The image snapped apart. The window was a window; the wind was only wind. The blizzard raged like any other blizzard, an act of nature.

But she couldn’t shake the restlessness in her middle. The urge to go somewhere, to be somewhere else, to be someone else, did not snap apart at the sound of the word Max. If anything, it grew worse.

IF JULIA WERE STILL a child back home with Gran, shut indoors during a storm, they would’ve popped up a bag of microwave popcorn and watched television until the power went out. Gran had a thing for horror movies. They calmed her nerves, she said. She said that if you experienced enough terror on the screen, real life was a walk in the park. But Julia and Victor had no television. They’d meant to get one, but Victor mostly entertained himself with books and medical journals, and Julia caught up with shows on her iPad. Last week, when the subject came up again, Victor had admitted he didn’t like having a television around, anyway. It made you lazy and indiscriminate; you would watch whatever was on just because it was on. Didn’t they have better things to do on a winter’s night, like go to bed early and keep each other warm? (Julia had to agree this was a much better idea.)

At the moment, though, Victor was at the hospital, caring for patients. Julia had already put a loaf of banana bread in the oven, and she wasn’t in the mood to settle down with a book. Her nerves were too frazzled, her head too full of images and ideas. The blizzard rattled the windows. She had to do something. She was driving herself crazy, pacing around the house. Jumping at every noise.

Julia went to the bedroom and pulled out her iPad, opened her Netflix account and searched for horror movies. She spotted something called Happy Death Day 2U, which sounded like something Gran would like, in the circumstances.

Back in the kitchen, she opened the pantry door, hoping to find some microwave popcorn. No popcorn, but she did discover a box of Swiss Miss. Just as she settled herself on the sofa with the iPad and a mug of hot chocolate, her phone rang. She snatched it up and looked at the screen.

Gran. Thank God.

“Guess what I’m doing,” Julia said.

“Baking cupcakes, maybe?” Gran ground out. Gran had grown up on a farm in Central California, making food from scratch, and she didn’t see why on earth Julia couldn’t just pick up a box of cookies from the supermarket and save herself the trouble.

“No,” Julia said. “I’m watching Happy Death Day 2U.”

“Happy what? Why the hell are you watching that?”

“Because there’s a blizzard outside. Don’t you watch the news?”

“The news said you were getting six to nine inches.”

“Well, the news is an idiot. It’s full-on Little House on the Prairie out there. Pa’s going to have to dig us a tunnel out the front door in the morning.”

“Pa? What about that boyfriend of yours? Can’t he dig a tunnel?”

“That was a joke, Gran. Anyway, Victor’s at the hospital. I’ll bet he gets snowed in himself. I don’t think even the Subaru can handle this.”

“What’s he doing at the hospital? Leaving you home alone in a goddamn blizzard, the louse. Just like your grandfather.”

“Gran, take it easy, okay? What’s the matter, did Gladys win the bingo tonight?”

“Gladys. That old bitch. You know she cheats.”

“Then why do you hang out with her?”

“Can’t live with her, can’t live without her. Besides, she keeps me on my toes. You young people have a word for it.”

“Frenemy?”

“That’s it.”

Julia set down her iPad on the coffee table and lifted the mug of cocoa. “I have a technical question, though. How exactly does somebody cheat at bingo?”

“Don’t sass me. I raised you from when you were in diapers, and my God, you knew how to fill a goddamn diaper.” Gran paused to suck on her cigarette. “Say, did you ever sort out that screwup at the library?”

Julia coughed on her cocoa. “Why do you ask?”

“I don’t know. Popped in my head just now. Library. Don’t worry, it’ll happen to you too. Get old sooner than you think. Thoughts pop in your head with no warning. Then—poof, it’s gone. Stand there in the middle of the bathroom and can’t remember why you’re there. Oh, it’s a real hoot, getting—”

“Gran, could you hold on a sec?”

“Excuse me? Hold on a sec? What am I, chopped—”

Julia trapped the squawking phone against her chest and went to the front door.

The wind wailed formlessly up and down. Beneath it, Julia heard the whisk of a billion tiny flakes of snow hitting the clapboard siding, the windows, the front porch. She laid her palm against the door and brought her ear right up to the vertical seam between door and frame. Gran’s voice vibrated against her wool sweater.

“—and that’s another thing—”

“Gran? Sorry. I just thought I heard something at the front door.”

Gran made a grunt of underestanding. “Something? Or someone?”

“Something, obviously. Only an idiot would be out in this.”

“Or a ghost.”

“Gran, please.”

“I’m serious. I was watching that Ghost Hunters show, you know the one where they go into some old dump at night with their fancy recorders and whatnot—”

“I know the show, Gran. We used to watch it together, remember?”

Another pause. “Well, shoot me. I guess we did, didn’t we? So you know there’s some crazy sh—”

“Gran!”

“Some crazy stuff out there.” Gran dragged on her cigarette. “If I were you, I’d make sure that door is locked tight.”

“Um, if it’s a ghost? Would that actually make any difference?”

“Don’t sass, I said. You never know. I mean, there’s all types of people, right? So it goes to figure there should be all kinds of ghosts. And they all want one thing from you, honey. One thing.”

“My virtue? My banana bread?”

“Jesus H. Christ. Do you want my advice or don’t you? No, don’t answer that. Of course you don’t want my advice. You’re young, you know everything already. Why am I wasting my breath?”

“I don’t know, Gran. You keep smoking those stupid cigarettes, you won’t have any breath left.”

“The Other Side, Julia. That’s what they want. They want to pass on over to the Other Side.” Gran smacked her gums. “And they’ll do whatever it takes to get there. Oh, fuddrucker.”

“What happened?”

“I just knocked over Gladys’s colostomy bag. Talk to you later.”

“What? How did you—”

The call went dead. Julia stared at the screen while the blizzard screamed on the other side of the wall. Was it her imagination, or did the wind seem wilder in the absence of Gran’s voice yakking in her ear? The empty house echoed around her. Her heart knocked against her ribs. You are ridiculous, she told herself. Too many horror movies. It was a dream, that’s all. Some dumb fantasy. You belong here in your house, nice and snug, not chasing off after some imaginary man you’ve never even—

BANG.

Julia startled and dropped her phone. The lights dimmed, then recovered. She bent to pick up her phone, and as she straightened, the room went dark.

“Hey Siri,” she said. “Turn on flashlight.”

A bright white beam burst from her phone. It’s on, Siri said placidly.

Julia cast the beam on the front door. A faint grinding noise came through the wind, like somebody starting a motorcycle. It flattened to a hum, and the lights came back on.

The generator. Of course! No self-respecting New England house came without a professional grade generator. When she and Victor first toured the place, the landlord had led them outside and showed off the big metal box like it was a new car, something about amps and kilowatts and fuel capacity. I wouldn’t try to run everything at once, now, he’d said, but it’ll keep your fridge going while you run a load of laundry, all right.

So there. Take that, blizzard.

Julia switched off the flashlight and texted Victor.

Power went out. Generator turned itself on. She added a thumb’s up and hit send.

She didn’t expect a reply. If Victor were making rounds or treating a patient, he wouldn’t touch his phone until had finished. He was finicky about germs, even at home. So she was surprised when the phone lit up a few seconds later with a thumb’s up and a dot dot dot, as he typed a response.

Keep that door locked ok? Then a red heart, of all things.

Julia’s eyebrows went up. Victor had always been good about kisses and cuddles and bringing home flowers; she had no complaints whatsoever about emotional availability. He’d just called himself her fiancé, for God’s sake! But still. He was not the heart emoji kind of boyfriend. He must’ve been pretty rattled to cross that line in the sand.

A warm feeling spread through her chest, chasing out the nerves.

Of course. Don’t worry about me. Julia replied.

She didn’t want to tax the generator, so she went around the house and flipped off any unnecessary lights. Her half-drunk mug of cocoa still sat on the coffee table next to the iPad, turning cold. She returned it to the kitchen and checked that the oven was still on. The comforting scent of banana bread had begun to spread through the air. She closed her eyes and breathed it in.

Everything was going to be all right. It was just a snowstorm! The thing with the library, that was just a weird mixup. As for the golden light and the room with the people in it, or whatever it was that had appeared in the crack between the books—well, that was just her imagination. Even now, when she tried to remember exactly what she’d seen, the scene had the hazy, bizarre quality of a hallucination.

And as for the man in the room, the dark-haired man who’d appeared in her dream—

“Miss Dalrymple?”

Julia spun around.

In the middle of the kitchen floor stood a tall, angular woman in a long wool coat and hat, dusted with melting snow. “I beg your pardon for barging in like this,” she said calmly, “but I don’t believe you heard me knock.”

LOOKING BACK, JULIA WOULD wonder why she took Dr. Freeman’s intrusion so calmly. Maybe it had something to do with the deaths of her parents, which had occurred when she was a baby, too young to remember the trauma, but nonetheless—this was what her psychology major roommate told her over late-night tequila, anyway—led her, at a subconscious level, to expect shocking events to occur without warning.

Or maybe she’d been waiting for her all along.

Instead of screaming or fainting or calling the police, Julia apologized to Dr. Freeman for not hearing her knock. She took her coat and hat and hung them up in the mudroom. The coat was long and beautifully tailored, made of the softest possible wool. Julia dragged her fingers along the sleeve as she hung it from the hook. When she returned to the kitchen, she offered cocoa. Dr. Freeman smiled and shook her head.

“Peppermint tea, maybe?”

Dr. Freeman’s brow creased, as if she’d never heard of such a thing, but she said tea would be lovely, thank you.

“I have some banana bread in the oven,” Julia said, as she put the kettle on, “but it won’t be ready for another half an hour, at least.”

“Oh, we won’t be that long, I assure you.”

Dr. Freeman sat at the kitchen table and watched her with narrowed, unblinking green eyes that reminded Julia of Gran’s black cat, the feral one she’d found prowling across the roof like a burglar one evening. She reached for the mugs and the tea bags. Dr. Freeman seemed puzzled by those, too. When Julia set down the mug before her, she lifted the string gingerly and sniffed the dry bag.

“Curious,” she murmured.

“The water won’t take a minute,” Julia said. She leaned back against the counter and drummed her fingers. The noise of the wind swirled faintly around them, but it sounded less angry now. Dr. Freeman crossed one leg over the other and roved the kitchen with her eyes. Something about her appearance tugged at Julia’s attention. She’d set an elbow on the table and propped her chin thoughtfully on her palm as she took in her surroundings. Her dark hair curled obediently around her ears, not a lock out of place. She had a long, firm neck that met the collar of her suit jacket in an impeccable line. No, you couldn’t fault her grooming.

A new, high note intruded against the blizzard’s wail, tentative at first, building in strength to a whistle. Julia realized it was the kettle. She crossed the kitchen floor and filled Dr. Freeman’s mug, then returned to the counter and filled her own. Dr. Freeman tugged at the teabag with her long fingers. She seemed absorbed by the swirls of steeping tea. After a moment she glanced at Julia, who pulled her own teabag free, wrapped the string around it to wring it out, and placed it on a saucer. She carried the saucer to Dr. Freeman, who’d just performed an identical maneuver with her own teabag. She set it on the saucer next to Julia’s.

As she turned to carry away the teabags, Julia realized what was so odd about Dr. Freeman’s appearance. She wore a different suit than she had at the library, less than two hours ago.

Julia looked back to be sure. The suit was made of wool the color of a dove’s wing, delicately pinstriped. The single breasted jacket buttoned over a cream silk blouse and a matching skirt that came all the way down to the middle of her calf. At the library, she’d been wearing olive. Julia was sure of it. She remembered it had brought out the green in Dr. Freeman’s eyes.

Julia took a tentative first sip of tea, burned her tongue, and set down the mug. “So. I’ve got to say, I’m dying to know what brings you here on a night like this.”

“A night like this?”

Julia nodded to the whitewashed window. “The blizzard and all?”

“The blizzard. Yes.” Dr. Freeman turned her head to watch the snow. “I think you know the answer to that, don’t you, Miss Dalrymple?”

“As a matter of fact, I don’t. I don’t know what the heck’s going on with you and the library and that Spooner guy and that—that whatever it is on the third floor.” Julia had started out calm, but with each word, her voice climbed closer to hysteria. She picked up her phone, which lay on the counter nearby, and brandished it. “And now my boyfriend tells me that the Darlington Library doesn’t even exist? What’s that about?”

Dr. Freeman sipped her tea. The heat didn’t seem to bother her a bit. “Of course the library exists. And I thought he said he was your fiancé.”

“That’s none of your business. All you need to know about Victor is that he knows how to do a Google search, and it turns out the Darlington Town Library closed in 1975.” Julia set down the phone and folded her arms over her chest.

“Did it? I wonder why.”

Julia threw her hands in the air. “Would you mind telling me what’s going on here? Who are you? And…and why did you change clothes like that?”

Dr. Freeman glanced down at her suit. “Dear me. Is something wrong with what I’m wearing?”

“Wrong? Everything about this is wrong! Why me? Why are you picking on me? I’m new in town, I haven’t done anything. Did I cut you off in traffic? Is this some kind of prank? Hazing the newcomer? Like a Vermont thing?”

Dr. Freeman rose from her chair and took a handkerchief from her pocket. “Now, Julia. May I call you Julia?”

“Seriously? Are you for real?”

“I’m very much real. Here you are.”

Dr. Freeman handed her the handkerchief, and Julia realized she was crying. Crying! It was humiliating. She wiped her eyes. The handkerchief was a real handkerchief, made from actual linen, snowy white.

“I didn’t mean to upset you,” said Dr. Freeman. “Of course you find all this a little strange. But if you’ll just trust me, Julia—”

“Trust you? Are you kidding me? Have you given me a single reason to trust you?”

“No, I suppose not.”

“You broke into my house, for God’s sake. I should call the police.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. For one thing, you know it wouldn’t do any good. I’d be gone by the time they arrived, and the police would naturally think you a lunatic.”

“They’d track you down. They have dogs and everything, you know. They’d follow your footprints in the snow.”

“No, they wouldn’t.”

Julia had stopped crying. In fact, she felt strangely peaceful. Maybe it was the tone of Dr. Freeman’s voice, which had the dulcet cadence of a trained therapist. Or was it the handkerchief, which smelled faintly of violets?

Violets. Just like upstairs in the damned library.

She sniffled once more and handed the handkerchief back to Dr. Freeman, who received it between the tip of her thumb and the tip of her forefinger and dropped it into the outside pocket of her suit jacket as if it were woven with threads of plutonium.

“Why not?” Julia said.

“Why wouldn’t the police find me? Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? Because I wouldn’t go where they were looking for me. I’d go where I belong.” She leaned forward. “Where you belong, Julia.”

Julia jumped back. “Me? I belong here! This is my house! I mean, technically it’s owned by the landlord, but It’s—”

“Julia, do stop warbling like this and listen to me. We don’t have much time.”

“—and this may come as a surprise, but I’m actually allowed to say who comes and who goes around here—”

“Tick tock, Julia.”

“—what I’m thinking is that it’s about time I asserted that right, once and for all, and what I’m trying to say is—”

“Are you quite finished?”

“—sayonara.”

“What?”

“Sayonara. Au revoir. Farewell. Cheerio, pip pip, off you go.” Julia made brushing movements with her hands. “Out the door. Go on.”

Dr. Freeman frowned at her. She checked her wristwatch and clicked her tongue.

“Very well,” she said. She turned on her heel and prowled her way across the kitchen to the mudroom. When she emerged a moment later, she wore her coat and hat, as before. She had also draped something black over her arm.

Julia’s down puffer coat.

“I suppose this will have to do,” she said.

“Now, wait a second—”

“We don’t have a second, I’m afraid. We don’t have any time at all. Are you coming, or not?”

“Where? To the library?”

Dr. Freeman started forward with the coat. “Chop chop. I’ll explain when we get there. It’s so much easier to show you than to tell you. Now, please—”

“Wait! One thing. Is it—is it something to do with the man in the room? The man with the dark hair?”

Dr. Freeman went still, hand outstretched. For a single, breathless second, nothing in the room moved at all. Only her stern eyes softened. “My goodness. So you do know, don’t you?”

“Know what?” Julia whispered.

Outside the windows, the blizzard made a last, high wail and fell quiet.

Dr. Freeman grasped Julia by the arm, just above the elbow, and dragged her to the pantry door. “Open it,” she said.

“But that’s the pantry—”

“Oh, for goodness’ sake.”

Dr. Freeman reached out and yanked the pantry door open.

Except it was not a pantry at all. Instead of shelves lined with the cans of crushed tomatoes and cannellini beans, the boxes of pasta and cereal, the bottles of seltzer and cranberry juice that she and Victor had hauled from Costco last month, Julia saw a night sky and a few swirling flakes of snow.

“Come along,” said Dr. Freeman. “There’s no time to lose.”

She stepped forward into the snow-scented darkness and pulled Julia after her.